THE WEEK THAT IT WAS...

The second full week of Q2 in the Jubilee Year was holiday-shortened, with most markets closed for Good Friday on April 18. Focus shifted to U.S. and Chinese retail and industrial data, central bank meetings in Canada and Europe, and earnings from 32 S&P 500 firms—including Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, UnitedHealth, and Netflix.

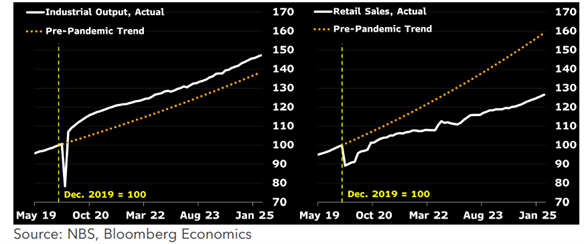

While the tariff tantrum continues to make headlines and rattle nerves, China seems to have missed the memo. Industrial production in March surged by a jaw-dropping 7.7% year on year, well above the 5.9% consensus. Retail sales also surprised everyone, climbing 5.9% compared to the modest 4.0% growth in January–February. The consensus was 4.3%. Clearly, someone forgot to tell the Chinese economy it's supposed to be struggling, even as the ‘Disruptor-in-Chief’ keeps insisting China is still a ‘peasant country,’ a notion eagerly lapped up by his MAGA crowd.

As expected from the ever-politically-attuned ECB chair, now earning kudos from the ‘Manipulator in Chief’ across the Atlantic, the ECB delivered its 7th consecutive 25bps rate cut, trimming the deposit facility, main refi, and marginal lending rates to 2.25%, 2.40%, and 2.65% respectively. The real plot twist? They finally ditched the word “restrictive” from the statement, because nothing says confidence like pretending monetary policy is suddenly neutral in the middle of an inflationary hangover.

The ECB also served up a predictably dovish outlook, citing “exceptional” uncertainty, because apparently, that’s the new normal. Justifying the cut, the Governing Council pointed to its “updated assessment” of inflation, underlying price dynamics, and how well monetary policy is supposedly working. While claiming the disinflation process is "well on track," they also admitted that growth prospects are dimming due to rising trade tensions. The reality, however, is that market indicators, which never lie contrary to central bankers, suggest the Eurozone remains firmly stuck in an inflationary environment while the economy teeters on the edge of another bust.

March U.S. retail sales rose 1.4%, largely reflecting consumers and businesses front-running tariffs ahead of "Liberation Day." While core control group sales increased a modest 0.4%, food service and restaurant spending rebounded sharply by 1.8%, reversing early-year weakness due to illness and weather. Overall, nominal spending likely rose 0.8% in March, with Q1 real consumer spending estimated at 0.8%, a slowdown from 4.0% in Q4 2024. The data suggests a mix of precautionary buying and selective recovery, with underlying caution still visible.

Inflation-adjusted retail sales rebounded in February from their lowest level since August 2024 but remain far below the April 2021 peak, a warning signal how the S&P 500 to Oil ratio hovers around its 7-year average. This suggests it's only a matter of time before the U.S. economy follows the rest of the world into a economic bust.

US Retail Sales Adjusted to inflation (i.e. CPI) (blue line); S&P 500 to WTI ratio (yellow line); 84-months Moving Average of the S&P 500 to WTI ratio (red line).

In a fireside chat at the Economic Club of Chicago, FED Chair Powell stuck to his favourite mantra—wait and see, insisting the FED is "well-positioned" to do absolutely nothing until things get clearer, whenever that may be. Stuck in his ‘transitory narrative’, Powell prefers to keep pondering trade-induced inflation and supply chain chaos. His big insight? Tariffs will probably mean higher inflation and slower growth—but hey, let’s just hope the U.S. banking system doesn’t implode in the upcoming ‘Trump Stagflation’ and inflation expectations remain anchored.

While Wall Street and the ‘Manipulator In Chief’ beg for an emergency rate cut and media cheerleaders fan the fear, markets cling to the fantasy that the increasingly toothless FED will save the day, pricing in more than three cuts by year-end, starting in June with 70% odds. But in reality, no cut may come, and the FED might even have to hike to salvage what’s left of its credibility as inflation bites back.

Active investors know trading isn’t just crunching numbers, it’s performance art with a touch of masochism. It takes skill, discipline, and the mental fortitude of a monk watching a tech stock crash. Markets don’t move on logic alone, they dance to the erratic rhythm of human emotion, hype, and herd mentality. Mastering this chaos? It’s all about timing, strategy, and executing your plan before your nerves execute you.

International trade isn’t a chess match, it’s poker with tariffs, bluffing, and the occasional diplomatic side-eye. Countries trade not out of love, but necessity (plus a dash of geopolitical showmanship). The winners? Those who read the room, dodge economic landmines, and fake confidence at global summits. In theory, it all rests on Ricardo’s 19th-century gem: comparative advantage. Do what you’re least bad at, trade the rest, and somehow everyone wins. Even the economic underachiever gets a trophy, as long as they specialize. It’s efficient, elegant, and works great… until someone flips the trade table.

David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage worked well under a gold standard, where trade imbalances were naturally corrected by flows of gold that constrained monetary expansion. However, the modern global trade system has drifted far from that model. Today, trade often involves one side exporting real goods and the other paying with fiat currency, especially U.S. dollars, which are accepted not because it represents an exchange of equal value, but because it was need to buy strategic resources like oil until USD assets were weaponized in 2022.

This imbalance is amplified by the United States' unique position of "imperial privilege," allowing it to run chronic trade deficits without facing the usual consequences. Instead of paying in kind, the U.S. issues dollar-denominated assets, essentially IOUs, which other countries accept and reinvest in U.S. financial markets. Over time, this dynamic has hollowed out American manufacturing, encouraging an economy focused more on consumption and financial services than on production. Meanwhile, other countries participate in the system by manipulating currencies, offering industrial subsidies, or exploiting tax loopholes through offshore hubs like Ireland. The result is a global economy where trade flows are less about comparative efficiency and more about who can best game the system. Instead of fostering mutual prosperity through productive exchange, the ‘pre-Liberation Day’ trade system rewarded financial engineering and leads to long-term structural imbalances.

https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/PP-1-31-12.pdf

Fast forward to the so-called U.S. Liberation Day on April 2nd, 2025: the ‘Disruptor-in-Chief’ unveiled what will go down in financial history books as Reciprocal Tariffs, a policy wrapped in the illusion of scientific rigor, supposedly based on U.S. import and export figures.

To simplify: if we swap his formula for 🍎 and 🍌, it becomes clear why penguins 🐧 in Antarctica are somehow being taxed. Why is this even considered reciprocal tariff calculation? This formula is clearly just a fancy way of stating: U.S. trade deficit / imports.

🍌 = exports, 🍎 = Imports.

Trump likely hopes to fix trade imbalances and U.S. deficits with tariffs. Admirable in theory… but impossible in practice, at least as long as the U.S. dollar remains the world’s dominant trading and reserve currency. Someone really should brief the administration on the Triffin Paradox: any country issuing the global reserve currency must run a deficit. That’s the price of power. The world needs more dollars than the U.S. can earn from exports alone, so the U.S. prints them, and voilà, its biggest export isn’t tech or oil, but money itself.

Tariffs might feel like action, but if pushed too far, they’ll end up taxing the U.S. out of reserve currency status. Classic case of “be careful what you wish for”, you just might get it.

Take China, for example: it runs a surplus with the U.S., but only because it imports raw materials to make the stuff Americans buy. A retaliatory tariff doesn’t mean China’s playing dirty, it just has a more efficient way of producing the Americans didn’t want to produce anymore. That’s the trade deal. The U.S. needed China’s low-cost goods, and China needed American consumers until it develops its own domestic consumer market. In return, China bought U.S. debt, once considered a safe bet but not anymore. As trust erodes, so do trade ties, and America’s partners are quietly heading for the exit.

Anyone with a sliver of common sense, and not currently starring in a trade war fantasy, knows global trade isn’t a perfectly balanced seesaw. Poorer countries don’t have the cash to splurge on U.S. goods. Their wages are a fraction of the U.S. minimum, which makes their products cheaper by default. No, Cambodia isn’t dreaming of Detroit sedans, and their factories won’t pack up and head to Ohio to dodge a 49% tariff. They’ll just find new customers who don’t throw tantrums over trade deficits. Imbalances aren’t a bug; they’re a feature of global trade. Treasury Secretary Bessent’s “Let them eat flat screens” line missed the point entirely. Yes, Americans got cheap TVs, but here’s the real kicker: these tariffs are scaring off investors. Because, shockingly, major companies don’t want to play economic isolationist cosplay.

While the financial media loves to chant that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff caused the Great Depression, that’s more fairy tale than fact. Yes, it made a convenient villain in Econ 101, but a look at the chart of U.S. tariffs since 1784: spoiler alert, Smoot-Hawley in 1930 targeted agriculture, not industry, and it wasn't exactly the first tariff rodeo. What the media, and Galbraith in The Great Crash, conveniently left out? The global sovereign defaults of 1931. But hey, why blame governments when you can point fingers at evil corporations instead? After all, Galbraith was a socialist, so businesses who create real wealth had to be the scapegoat. Sure, some argue Smoot-Hawley contributed to the Depression. That’s the diplomatic way of saying “it didn’t help.” But saying it was the cause while ignoring the avalanche of sovereign debt defaults? That’s just bad history. Smoot-Hawley didn’t even become law until June 17, 1930, by then, the stock market had already plunged from its September 1929 peak. Yes, traders may have anticipated it, as Cato’s Alan Reynolds pointed out. But does that mean the market would’ve kept soaring “but for” the tariff talk? Come on. As if a single bill derailed an entire global economy already drowning in debt and denial.

In a nutshell, the idea that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff caused the Great Depression while ignoring the European Sovereign Debt Crisis is a weak argument. Tariffs like the 1921 Emergency Tariff and Fordney-McCumber Tariff were already in place, pushed by nationalism and protectionism after World War I. These measures, aimed at protecting U.S. prosperity, predate Smoot-Hawley and were part of a broader trend of isolationism.

The real problem wasn’t tariffs, it was DEBT. From 1927 to 1929, as signs of a European debt crisis emerged, investors shifted from bonds to equities, causing a ‘Phase Transition’ in markets, where capital concentrated in specific sectors and countries, leading to massive price increases. This wasn’t just inflation; it was a fundamental shift in capital.

Irving Fisher, a prominent economist, lost credibility when he claimed the market had reached a new plateau and wouldn’t crash. He misunderstood the shift from bonds to equities, which can be termed a "Phase Transition." The shift from bonds to equities can lead to a new plateau, provided it occurs gradually as a trend. When it erupts in the short term and causes a doubling of prices, it’s a warning sign that we’re dealing with a bubble, not a broad shift in the investment trend.

To understand the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs, often blamed for contributing to the Great Depression, we must consider the broader global and domestic economic context. In 1927, there wasn't just a secret meeting among central banks to lower U.S. interest rates to deflect capital flows back to Europe, but also the League of Nations’ World Economic Conference in Geneva, where it was officially decided that tariffs should be reduced. Despite this, France, resentful of Germany, broke ranks and enacted new tariffs in 1928, targeting Germany. These tariffs were designed to block Germany from making reparation payments imposed after World War I. The German people, punished for the actions of their political leaders, faced harsh economic conditions. This resentment contributed to the rise of Hitler, as the French failed to differentiate between the German government and its people.

On the other side of the pond, the economic shift in the early 20th century, driven by the advent of electricity and the combustion engine, transformed the U.S. economy. In 1900, around 40% of the workforce was in agriculture, but by the late 1920s, productivity soared due to electrification and agricultural innovations like tractors replacing horses. This freed up significant land previously used for feeding animals, increasing food production and leading to overproduction and underconsumption. Senator Reed Smoot, a Republican from Utah, and Congressman Willis C. Hawley, a Republican from Oregon, were responding to demands from farmers, particularly in non-industrial states, for high tariffs to protect them from falling prices. However, the issue wasn’t imports, it was overproduction. Smoot-Hawley aimed to shield farmers from this challenge, similar to how the Silver Democrats had supported miners in the late 19th century.

Meanwhile, the U.S. was still running a trade surplus due to rising manufactured exports after World War I, while food exports declined as Europe rebuilt its agricultural sector. The farmers' struggles were more about this shift in agricultural dynamics than concerns over foreign competition. Smoot's support for the tariff increase in 1929, which became the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, reflected his belief that the world was paying for the destruction caused by the war and the failure to adjust purchasing power to new industrial realities. However, he overlooked the profound economic changes brought on by technological advancements like electricity and the combustion engine.

In the 1928 Presidential election, Herbert Hoover promised to support farmers by increasing tariffs on agricultural goods. After winning, Hoover asked Congress to raise tariffs on agriculture while lowering them on industrial products, aiming for a balance to satisfy trading partners. In May 1929, the House passed a version of the tariff bill, focusing on agricultural goods. Critics of the Smoot-Hawley Act argue that the market crash of 1929 was triggered by the bill's passage on May 28th. However, this claim is inaccurate. The bill passed on May 28th, which coincided with the market's low point, but it wasn’t the cause of the downturn. The real catalyst was the British elections on May 30th, which resulted in a hung Parliament, seen as a political crisis. The very next day, Ford Motor Company signed a significant contract with the Soviet Union, further distancing the market response from the tariff bill. The market reaction was more influenced by these events than by the tariff debate, and there was a clear distinction between the impacts of agricultural versus industrial imports.

Dow Jones Industrial Average between December 1927 and December 1932.

Those who blame tariffs for the 1929 crash point to October 23rd, when it seemed tariffs would be broader than expected. However, no headlines support this narrative. On that day, bankers tried to stabilize the market, but their failure caused a collapse in confidence. Additionally, an assassination attempt on the Italian Crown Prince heightened American concerns about Europe's instability. The tariff argument was pushed by Democrats, similar to their later critiques of Reagan’s "trickle-down" economics. Some senators, including William Henry King, called for investigations into the Federal Reserve and proposed tax hikes on stock sales. Senator Carter Glass pushed for a 5% excise tax on stocks held for less than 60 days, which he tried to attach to the tariff bill. Focusing on tariffs as the cause of the crash is misguided—what truly concerned investors was the proposed tax on stock investments, not the tariffs themselves.

The US Senate debated the tariff bill until March 1930, with Senators voting based on their states' interests. The bill passed with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats from farming states. The conference committee then aligned the Senate and House versions, moving to the higher House tariffs. The final bill passed the House 222-153, supported by 208 Republicans and 14 Democrats, primarily influenced by farmers. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, signed into law on June 17, 1930, implemented protectionist policies. However, when the law was enacted, no significant headlines predicted an economic collapse. Bankers again attempted to stabilize the market, but no commentary blamed the tariffs for the market's decline. Democrats used the tariff as a political attack against Republicans, but the true cause of the crash was the default on sovereign debt sold by investment banks to the public, wiping out savings and causing widespread bank defaults. Spending cuts, particularly in the military, and the tariff issue further fueled political debates, with many in Congress critical of European demands for free access to U.S. markets while blocking theirs. The tariff debate stemmed from agricultural overproduction during the transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy, which politicians struggled to grasp. In 1931, bankers' failed attempts to stabilize the market led to a loss of confidence in both the government and the financial system. Investors were scrutinized, and the Senate held hearings on stock market practices. On March 2, 1932, the Senate authorized an investigation into the buying, selling, and lending of stocks, but the committee made little progress, as banking executives denied requests for documents and witnesses evaded questions.

The same tired playbook was used in 1932, blame tariffs, blame Hoover, and hand FDR the keys to the White House. It was a political con job then, just as it is now. The idea that tariffs caused the Great Depression is a fabrication, peddled by Democrats in 1932 to win an election and now revived in a desperate attempt to impose more malthusian keynesian policies. The media is running the same script: crash the market, blame the outsider, and protect the gravy train.

Never mind that tariffs were being raised globally well before the 1929 crash; 33 major hikes between 1925 and 1929, from Europe to Latin America to Asia. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand got in on it too. Somehow, all that vanished from the history books, along with the 1931 wave of sovereign defaults that actually shattered confidence and wiped out savings. But sure, let’s keep pretending a tariff on sugar and shoes brought down the world economy.

In summary, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 wasn’t the spark that lit the protectionist fire, it was a reaction to the one already burning. The real trade war started before 1929, when Europe, fresh from the wreckage of World War I, tried to claw back its pre-war economic dominance. Capital and production had fled to the U.S. and Latin America during the war, and Europe wasn’t pleased. Take sugar, for example. European production collapsed during the war and shifted to Java, Cuba, and South America. Prices spiked in 1919/1920. But after the war, Europe slapped on high tariffs to push back against these new competitors. The result? Sugar production in Europe not only returned but exceeded pre-war levels by 1927–1928. They pulled the same stunt with cotton and wheat, tariffs that led to overproduction and the loss of export markets. This was the true face of the protectionist wave. But instead of acknowledging that Europe kicked off the trade war to protect its own industries, history pins it all on Smoot-Hawley, because, of course, it makes for a cleaner, more convenient scapegoat.

Outside the U.S., the real shock to the global economy came not from tariffs but from cascading debt defaults. On May 11, 1931, Austria’s largest bank, Creditanstalt, collapsed—triggering a full-blown currency crisis as panicked investors pulled funds from Austrian banks and moved them abroad. Meanwhile, Germany was slipping into political chaos. Just days earlier, on May 8, Hitler had slipped past a legal challenge by Hans Litten, who had tried to hold him accountable for SA violence. Litten would later be arrested after the Reichstag fire and spend years tortured in Nazi camps before taking his own life. His story is haunting—and a grim reminder of what the world was really confronting. To say that tariffs caused the Great Depression? That’s the kind of simplistic scapegoating that made for great Democratic campaign fodder in 1932, but it doesn’t hold up. The real destruction came from the collapse of Sovereign Debt, bonds sold in small denominations to everyday people who thought they were playing it safe. They avoided stocks, only to lose everything when governments defaulted. Unlike stocks, which eventually recovered, these bonds went to zero and stayed there. Even U.S. municipalities like Detroit stopped paying—Detroit paused payments in 1937 and didn’t resume until 1963, just so they could technically say they never defaulted. While the Dow fell 89%, bonds fell 100%, and never came back. But sure, let’s keep blaming tariffs and believe that government debt is a safe haven.

A look at the 1980s, Reagan’s America, the trade deficit was rising, but the economy was booming, go figure. Volcker’s sky-high interest rates didn’t just crush inflation, they also pulled in foreign capital like moths to a flame. The dollar skyrocketed, even sending the British pound scrambling to keep up in 1985. Meanwhile, interest payments on the national debt, totally unrelated to goods or services, were flowing out of the U.S., showing up in the current account.

Dow Jones Index (blue line); FED Fund Rate (red line) between December 1970 and December 1984.

Once upon a time, in a slightly more united States of America, tariffs weren’t just a red-versus-blue shouting match. In fact, long before Trump turned trade wars into reality TV, none other than Nancy Pelosi, yes, that Nancy, was waving the anti-China tariff flag like a proud protectionist.

Back in 1996, Pelosi stood on the House floor decrying the “cruel hoax” of U.S.-China trade. With a passion usually reserved for insider stock tips, she warned of lost jobs, unfair tariffs, and a $34 billion trade deficit ballooning faster than a congressional budget. China, she argued, was eating our lunch, while we politely footed the bill. Her solution? Tariffs. Lots of them. Reciprocal ones. The U.S. was charging 2%; China was slapping us with 35%. Pelosi was outraged. She even brought charts. You know it’s serious when the PowerPoint comes out. Fast-forward to 2025, and suddenly tariffs are “reckless,” “chaotic,” and “the largest tax hike on Americans in history”, but only because the guy proposing them now is named Trump, not Clinton. What changed? Not China. Not the trade deficit. Just the face on the policy. Pelosi’s pirouette is a masterclass in political flexibility, yoga instructors could only dream of that kind of bend.

Turns out, when it comes to tariffs, it’s not about jobs, deficits, or even China—it’s about who’s in the Oval Office. And as always, consistency in politics is about as common as a balanced budget.

Most people, and let’s be honest, most politicians can not tell the difference between the current account and the capital account if their next campaign donation depended on it.

Here’s the deal: the U.S. runs a trade deficit, and everyone freaks out like it’s a sign of economic doom. But guess what? That’s only half the story. The capital account is the other half, and it’s flushed with foreign money flowing into the U.S. to buy everything from Treasuries and stocks to real estate and tech startups. You sell Apple shares to a Swiss pension fund? Boom, that’s a capital inflow. US company repatriating overseas profits? More dollars in. Now, the current account isn’t just goods and services. It includes income flows, dividends, interest, corporate profits, sent to and from foreign investors. So when the US government sells Treasuries to China, and pay them interest on their $1.1 trillion stash, that adds to the current account deficit. At $1 trillion in total US interest payments, that’s $100 billion in transfers to Beijing alone. But let’s not pretend tariffs will magically fix that.

In fact, tariffs might push foreign investors to sell U.S. assets and take their capital home, shrinking the capital account surplus, and yes, reducing the current account deficit. Not because the ‘Manipulator In Chief’ won the trade war", but because he scared off the capital flows. So next time someone yells “Trade Deficit!” like it’s the end of days, ask them if they’ve ever heard of the balance of payments. Odds are, they haven’t, and they probably sit on a subcommittee.

Even inside the U.S., companies are packing their bags, not for China, but for Texas. Or Florida. Or any state where taxes don’t eat your margins alive. Take Michigan, for example. Sure, they replaced the dreaded Michigan Business Tax in 2011 with a more "friendly" 6% corporate tax rate, but add Detroit’s 2% city tax and you're quickly staring down 8% before Uncle Sam shows up with his federal cut. That’s a pretty tough sell when states like Wyoming or South Dakota are out there whispering sweet nothings like “no corporate income tax.” Now zoom out: U.S. manufacturers didn’t just vanish overseas, they were pushed. Local and state income taxes piled onto federal taxes like an IRS sandwich. And let’s not forget the cherry on top: a Supreme Court decision that blessed worldwide taxation on American citizens and businesses. So yes, the U.S. is basically the only country that taxes you no matter where you go, like the clingiest ex in history.

Keynesians love to paint corporations as villains who offshored for cheaper labor. But in reality, it’s not about paying $10 instead of $20 an hour, it’s about paying five figures to accountants, lawyers, and compliance teams just to survive the U.S. tax maze. And if the IRS sniffs even a whiff of "contractor" vs "employee" mislabeling? Say hello to an audit, and goodbye to $25,000 in legal and accounting fees even if you win. It's not greed. It's tax survival.

Tax rate per US states.

While tariffs aren’t the root of a depression, despite what political mythology keeps recycling, the costs still land squarely on the backs of consumers and entrepreneurs. And now, courtesy of the 47th president, we’re getting a fresh round of economic self-harm wrapped in patriotic rhetoric. Call it what you like, but a tariff is just a tax in disguise, no matter how skillfully it's sold as a blow against foreign adversaries.

‘Liberation Day’ tariffs are poised to hit tech, media, and telecom (TMT) the hardest. Communications segments like interactive media and diversified telecoms, already highly exposed to China, could face brutal extra duty. Chemicals, too, are in the crosshairs. Meanwhile, textiles, dependent on Vietnam and India, are looking at penalising levies. In short: this isn’t a trade war. It’s a silent tax hike dressed up as economic nationalism.

Mid-cap stocks could be in for a rougher ride in a tariff-heavy environment. Based on cost of goods sold (COGS), the S&P 400’s tech and industrial sectors are far more exposed to foreign inputs than their larger-cap peers, making them more tariff-sensitive and potentially weaker performers ahead. Tech leads the vulnerability list, with 69% of its input costs sourced overseas, followed by industrials at 59%. In comparison, S&P 500 tech and industrials clock in at 78% and 41.5%, respectively. Most other mid-cap sectors rely more heavily on U.S. inputs, though discretionary (46%) and materials (42%) still carry meaningful foreign exposure. On the other end of the spectrum, consumer staples (6%) and health care (7%) barely flinch. In short: tariffs might sting across the board, but mid-cap tech and industrials are standing closest to the fire.

Mid-cap stocks could take a disproportionate hit from reciprocal tariffs, especially from Canada and the EU. While the S&P 400 generates just 19.1% of its revenue abroad, less than the S&P 500’s 29.6%, that exposure is highly concentrated. Canada leads the list at 11.3%, followed closely by Germany (11.2%) and France (10%). Other notable exposures include China (8.9%), Brazil (6.3%), Mexico (5.7%), Italy (5.6%), and the UK (4.2%). So, while mid-caps are less global on paper, they’re more dependent on a handful of key foreign markets. If these countries respond in kind to new U.S. tariffs, American products could get priced out—just when everyone’s trying to sell more abroad.

Coming back to the art of the trade, the average S&P 500 stock now sees just under 17% of its shares held by active mutual funds and ETFs, down from over 21% a decade ago. The passive tide has washed over large-cap U.S. equities, and it's showing. On a weighted basis, active ownership dips even lower, to just 14%, suggesting that active managers are underweighting the mega-caps and fishing further down the size spectrum. In other words, while passive funds keep pouring into the Apples and Amazons, active managers are quietly hunting value in the shadows.

For once and foremost, the entire Tariff Issue of the 1930s was just political. The Democrats used it to beat the Republicans over the head and pretended that the Tariffs caused the Great Depression. Today, we have the media, which hates Trump as they all tried so hard to defeat him, now they are deliberately blaming tariffs all over again for a normal correction that many kept calling for a major crash before tariffs. Investors must understand that Tariffs do not cause a DEPRESSION, no matter how much the media is selling that story now. It is the default in sovereign debt which is creating a depression and tariff will only contribute to the natural evolution of the business cycle from the inflationary boom which prevailed since 2023 in the US into an inflationary bust which is the natural evoltion of how the business cycle works even if the keynesian dream has and has always been to control the busines cycle.

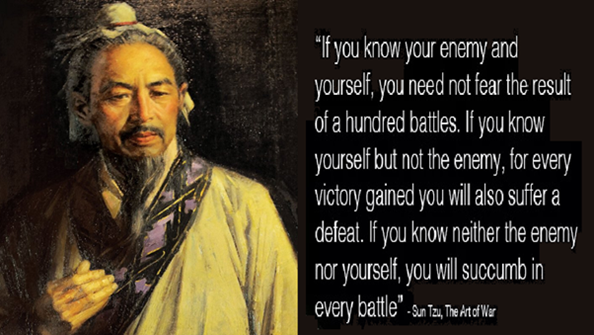

At the end of the day, while the 47th U.S. president was initially famous for his 'Art of the Deal,' those in the Eastern world have been trained to study the ‘Art of War’ by Lao Tzu. This timeless wisdom could serve investors well, as mastering 'The Art of the Trade' requires knowing both yourself and your enemy. With that knowledge, you need not fear the outcome of a hundred trades.

In this context, savvy investors understand that to preserve and grow their wealth, they must adapt to the business cycle rather than trying to change it. Indeed, investors must focus on safeguarding their wealth by owning real assets like physical gold and silver, the only antifragile assets with no counterparty risk. Investors should also focus on Return OF Capital rather than Return On Capital, holding other commodities to weather the storm unleashed by the ‘Commodity Leviathan.’ Additionally, they will actively manage their cash allocation using a portfolio of short-dated, investment-grade (IG) USD bonds with maturities under 12 months and Treasury bills (T-bills) with maturities not exceeding 3 months. These income-generating assets will provide stability. Among equities, investors should continue favoring low-leverage companies with strong EPS and FCF growth, prioritizing energy and commodity producers over consumers. By doing so, investors will ensure both peace of mind and wealth preservation.

WHAT’S ON THE AGENDA NEXT WEEK?

The third week of the first month of the second quarter in this Jubilee Year, will be another holiday-shortened trading week in Europe due to Easter Monday. With a relatively light macroeconomic calendar, markets will focus primarily on updated consumer sentiment and inflation expectations. Meanwhile, the spotlight will shift to corporate earnings, with 117 S&P 500 companies scheduled to report first-quarter results. Key names to watch include Lockheed Martin, RTX, Northrop Grumman, Tesla, Philip Morris, Freeport-McMoRan, and Alphabet.

KEY TAKEWAYS.

As investors heroically juggle chocolate egg hunts and bunny sightings, the key takeaways are:

China's Retail Sales just blew past expectations apparently no one told them they're supposed to be ‘struggling peasants’ but more time is needed to ‘Make China Great Again’.

The ECB cut rates for the 7th time, dropped “restrictive” from its stance, and called inflation tamed, while the Eurozone edges closer to stagflation and a fresh downturn.

March retail sales reveal a tariff-fuelled sugar high masking deeper weakness, as cautious consumers, fading momentum, and a flashing S&P 500-to-Oil ratio warn the U.S. may soon join the global slowdown.

Investing is a mental game of timing and strategy, while international trade is a high-stakes poker match where reading the room and playing your hand can win the day, until the table flips.

Blaming the Smoot-Hawley Tariff for the Great Depression is a convenient scapegoat, ignoring the real culprit: the global sovereign debt crisis that had already set the stage for economic collapse.

The U.S. trade deficit isn’t a crisis, it’s balanced by foreign investment, and tariffs could just scare that money off.

U.S. companies aren't just offshoring for cheap labour, they're fleeing bureaucratic rules and a complicated IRS maze that makes survival, not greed, the real motivator.

Tariffs may not cause a depression, but they are a hidden tax, hitting U.S. mid-cap stocks, particularly tech and industrials, hardest as they face higher costs and foreign retaliation.

As the US economy shifts into an inflationary bust, investors will once again need to focus on the Return OF Capital rather than the Return ON Capital, as stagflation spreads.

Physical gold and silver remain THE ONLY reliable hedges against reckless and untrustworthy governments and bankers.

Gold and silver are eternal hedge against "collective stupidity" and government hegemony, both of which are abundant worldwide.

With continued decline in trust in public institutions, particularly in the Western world, investors are expected to move even more into assets with no counterparty risk which are non-confiscable, like physical Gold and Silver.

Long dated US Treasuries and Bonds are an ‘un-investable return-less' asset class which have also lost their rationale for being part of a diversified portfolio.

Unequivocally, the risky part of the portfolio has moved to fixed income and therefore rather than chasing long-dated government bonds, fixed income investors should focus on USD investment-grade US corporate bonds with a duration not longer than 12 months to manage their cash.

In this context, investors should also be prepared for much higher volatility as well as dull inflation-adjusted returns in the foreseeable future.

HOW TO TRADE IT?

The four-day week following the Good Friday holiday will be remembered as a week of consolidation in equity markets, as investors await the second wave of the ‘Tariff Tantrum’, which had triggered a bout of financial madness the previous week. After posting their best weekly returns since June 2022, U.S. equity indices pulled back, with the S&P 500 outperforming both the Nasdaq and the Dow Jones, while the Magnificent 7 are increasingly starting to look like the ‘Maleficent 7’. With all major U.S. indices once again breaking below their respective 38.2% Fibonacci retracement levels of the 1-year chart (5,336; 18,712; 39,844), and with both momentum and stochastic indicators rolling over, an intraday retest of the April 8th closing levels has once again become the most likely scenario, before the dust settles and markets potentially form a sustainable double bottom, signalling a rebound in the second half of the year. Any daily close below those levels would suggest the ‘Tariff Tantrum’ will get worse before it gets better. However, the April 8th closing prices (4,982; 17,090; 37,645) appear to be the most likely support level and potentially a tradeable bottom. If confirmed and followed by higher lows, indices like the Dow could be on track to hit new all-time highs in the second half of the year. As of April 18, all major U.S. indices remain in daily and weekly bearish reversals, with stochastics indicating that daily higher lows will be required to confirm that the lows of the year were indeed reached intraday on April 7th.

In this context, Energy; Real Estate and Materials outperformed, while IT; Communication Services and Consumer Discretionary underperformed.

As of April 18th , 2025, the US remains in an inflationary boom, but with the S&P 500 to Gold ratio now below its year below its 7-year moving average for almost 3 months, an inflationary bust will materialize much sooner than Wall Street pundits and their parrots are eager to tell their clients. In this context, investors should stay calm, disciplined, and use market data tools to anticipate changes in the business cycle, rather than fall into the forward confusion and illusion spread by Wall Street.

In an increasingly multipolar world, mastering the art of the deal, war, and trade will no longer be optional, it will be essential. Whether you're an investor or not, survival, both financial and physical, will depend on your ability to navigate the shifting tides of global power. The first step is clear: remain open-minded, humble, and nimble.

Those who wish to preserve their health and wealth through the coming business and war cycles must prioritize relocation or alignment with nations that are antifragile, those that possess self-sufficiency in food, energy, and manufacturing. Countries that have grown dependent on fragile international supply chains and have forfeited domestic resilience will suffer disproportionately as global fragmentation accelerates.

Wealth built upon outdated business models born of the now-fading unipolar, globalist order stands at grave risk. It may be annihilated entirely, especially in nations whose leaders remain blind to the seismic shifts underway.

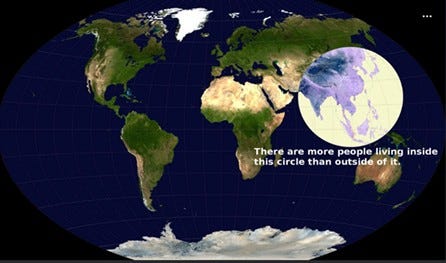

Xi knows exactly what time it is: China’s entered a long, grinding standoff with both the U.S. and Europe, on trade, tech, and territory. The wake-up call came when the West went full throttle against Russia, and Biden’s team warned China not to follow suit. Since then, Xi’s been gearing up for confrontation. Blinken, playing the global hall monitor, raised “serious concerns” about China aiding Russia’s defense industry, and not-so-subtly threatened sanctions if Xi crossed the line. The reality is that the combination of Russia, China, and ultimately India will create an invincible economic bloc, combining cheap access to commodities from Russia, state-of-the-art manufacturing and affordable funding from China, and a consumer-driven economy supported by favorable demographics in India. Neighboring nations that recognize this emerging reality, many of which lie within the Valeriepieris Circle, may share in the prosperity of this new era. But not all will benefit. Countries like Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and even Singapore risk marginalization if they continue clinging to the vestiges of U.S. hegemony and refuse to recalibrate their strategies for a world that has already begun to change.

American neocons, blinded by imperial ambition, have dangerously underestimated the economic fallout of threatening China and kicking Russia out of SWIFT. This fractured the global system and accelerated the rise of BRICS as a geopolitical counterweight. Trump may talk tough on China to revive U.S. manufacturing, but he seems unaware of the broader consequences. Foreigners once held more than 33% of US government debt with China alone holding more than 10%, which it has quietly been selling. In January alone, foreigners sold $13.3 billion in long-term Treasuries. December 2024 saw a $50 billion dump in anticipation of Trump’s trade war. Japan, the UK, and Canada led the recent selling, desperate for liquidity as these countries edge closer to sovereign default. The real danger for Americans isn’t the Houthis or cheaper goods on supermarket shelves, it’s China. A large-scale dump of U.S. debt could trigger a bond rout, send long-term interest rates soaring, and ultimately make it impossible for the average American to buy a house or a car. For now, China isn’t reacting. It’s executing.

Percentage of Non-US Investors holding US Government debt.

Behind the scenes, during the ongoing ‘Tariff Tantrum’, U.S. Treasury yields have been rising during overnight sessions, signaling foreign selling in particular from Asia. Still, the threat of war in Europe does not yet point to a collapse in U.S. bonds as conflict tends to drive capital into the US and Treasuries will likely benefit somewhat of the upcoming escallation of the geopolitical events in Europe and the Middle East. As Sweden and Switzerland abandon their ancestral neutrality, neither will serve as a safe harbor for capital during war, unlike in World War I and II. This leaves the USA as the sole refuge for significant capital from the Western world. In this environment, physical gold remains the only truly antifragile asset. Meanwhile, as Wall Street and politicians misuse tariffs for political theater, investors will steer clear of government bonds, especially those with maturities beyond six months, and look to add Dow Jones equities during the current correction.

Relative Performance of Dow Jones to US Treasury Index (blue line); Gold to US Treasury Index (red line) rebased at 100 on December 31st, 1973.

Finaly, investors understand that markets are driven by opinions, where every buyer believes they’ve found a bargain, and every seller has their reasons for parting ways with an asset. But let’s set the record straight: investors MUST IGNORE the panic-peddling, politically motivated financial media claiming that tariffs will end not just the equity bull market, but civilization itself. The fear-mongering that investors will lose everything in their 401(k)s due to tariffs is not just misguided, it's downright criminal. The real threat in this environment is far deeper and more insidious than any tariff debate.

By owning physical gold outside the tightening grip of centralized digital systems, the “old-fashioned” gold holders preserve true autonomy, not just from the USD, but from all fiat currencies racing toward centralization.

Gold in private vaults comes with no compliance protocols, no digital IDs, no counterparty risk, and no reliance on other politically exposed, centralized infrastructures. Unlike digital assets born in 2008, gold protects not just from currency collapse, but also from volatility and centralization. It’s been doing so since 480 BC. That matters. Gold matters—yesterday, today, and especially tomorrow.

If this research has inspired you to invest in gold and silver, consider GoldSilver.com to buy your physical gold:

https://goldsilver.com/?aff=TMB

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.

Very well written and interesting! IN regards to Ricardo's comparative advantage, at least from the political and economic revolution of the Jacksonians during the 1830s and on, 19th century America's economic architectural design not only rejected it in relation to itself vis a vis but also, and this is fascinating as I never truly appreciated either the extent or the many small but collectively very powerful nuances of it, it also rejected it inside of itself.

I decided to revisit the period of American history known as the 'Bank War'. After having read five books on it, in order to find out what it was really about I had to pay to access a wide partisan range of papers from the time and then also look through us state level legislative records, and theres something telling about that.

The 'Bank War' was about capital formation, banking and finance regulations, and development economics. California was very close to having a development economics program applied to it that was almost the same as the one that has been applied to the Congo for the past fifty years. Complete with "regulatory harmonization", strict and nonnegotiable economic/legal structures that asserted the concepts of comparative advantage and a highly precise American continental division of labor. Well, we've seen the results.

Using Massachusetts as microcosm, Worcester Ma -- a socio-economic political community -- gaining the ability to, within limits, for the most part dictate the deployment of *its own* area capital led to huge investments in everything from new infrastructure and businesses and a high quality technical academy called WPI (at first a predecessor programs(s) to it) and lots else.

I also learned about a very powerful and stark moral dimension to banking and financial architectures that I never quite knew existed. You mentioned the 1980s as a boom time. But its 1) highly debatable that "demand destruction" solved inflation, a string argument can be made that it was massive new amounts of energy and metals production being brought online. But the big moral dimension is that some large areas around the country, such as swaths of the Midwest which were reeling from a heat wave that is to this day the most economically destructive (in dollar terms at least) natural disaster in the nation's history, was denied the abilit to use its own capital to sustain itself economically and the negative effects were deep and generationally lasting.

There a few points but I dont have time here. Your review of smoot hawley is real good and you brought up some specific events related to it I never knew about, thanks for writing it.

I hope your having a nice weekend. --Mike

Who is John Galt?