THE WEEK THAT IT WAS...

The last full week of the first month of the final quarter of the year was relatively quiet in terms of macroeconomic data, with the BRICS Summit in Kazan, likely being the most important event not only of the week but also a pivotal moment for decades to come. In the US, investors focused once again on the flash estimates of the S&P US Manufacturing and Services PMI and another estimate of the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment and inflation expectations. On the other hand, the week marked the first leg of the ‘Super Bowl’ of the Q3 2024 earnings season, with 37% of the S&P 500's market capitalization reporting earnings, including one of the so-called Magnificent 7.

At the Kazan BRICS summit, China and India, under Russia's patronage, settled their border dispute in a ‘diplomatic coup.’

By combining China’s manufacturing power, India’s consumption demand, and access to Russia cheap fossil energy, these countries are laying the foundation for exponential mercantilist growth across the Global South. Developing economic corridors, the three BRICS pillars (Russia, India, and China) will drive prosperity in the Global South, benefiting ASEAN and Middle Eastern nations which are joining the alliance, while those tied to the Malthusian Western world will inevitably fall into underdevelopment.

In the US, while both Manufacturing (47.8 vs. 47.3 prior) and Services (55.3 vs. 55.2 prior) survey data were better than expected (47.5 and 55.0, respectively), the manufacturing sector remains in recessionary territory (below 50). Businesses remain cautious about hiring, leading to a third consecutive month of modest payroll reductions, with particular concern about uncertainty caused by the Presidential Election.

US Manufacturing PMI Index (blue line); US Services PMI (red line).

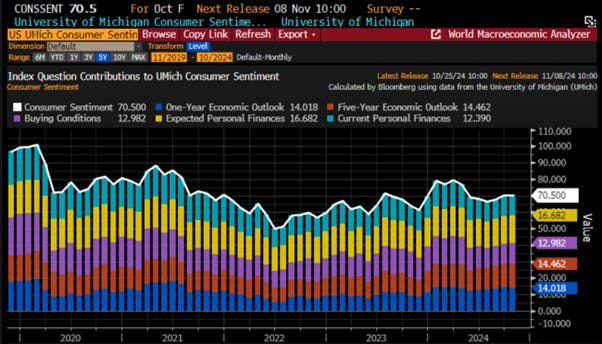

October's final University of Michigan Sentiment survey exceeded expectations, rising to 70.5 (from a preliminary 68.9), marking the highest level since April 2024. This boost stemmed from improved durable goods buying conditions and the perceived impact of recent FED rate cuts.

The October Beige Book, now seen as the bible for the partisan driven FED chairman, revealed little change in economic activity, with modest growth in only two Districts and declines in manufacturing. Consumer spending shifted toward cheaper goods, suggesting more inflation driven misery for lower-income consumers. While banking and housing remained stable, mortgage uncertainty deterred some buyers. Commercial real estate was flat, except for growth in data centres, and both agriculture and energy sectors faced challenges. Labor markets showed slight growth and improved worker availability, though skilled labour shortages persisted. Inflation moderated, but input costs outpaced selling prices, squeezing profit margins due to rising insurance and healthcare expenses. A semantic analysis indicated minimal changes in the FED's key metrics: inflation-related terms rose slightly from 11 to 12, while discussions of economic slowdown remained unchanged at 55.

Bottom line: If the September Beige Book influenced the FED's 50bps cut as the FED chairman proclaimed, the October Beige Book reinforces that trend without significant changes. Savvy investors recognize that rather than relying on politically motivated economic data; market data offers a more reliable assessment of the economic landscape. Currently, the US economy is experiencing an inflationary boom, as indicated by the SPX/WTI ratio remaining above its 7-year moving average and the Gold to Government bond ratio consistently exceeding that average since the decade began. However, with the SPX/Gold ratio recently breaking below its 7-year moving average, investors should brace for a shift from an inflationary boom to an inflationary bust, likely triggered by escalating in the war cycle in the Middle East before the inauguration of the 47th US President.

History shows that once the S&P 500/WTI ratio breaks below its 7-year moving average, every equity rally should be sold.

Upper Panel: S&P 500/WTI ratio (green line); 84 months Moving average of the S&P 500/ WTI ratio (red line); Lower Panel: S&P 500 index 12-month Rate of Change (yellow histogram).

Investors should then focus on buying the dips in energy producers while selling the strength in energy consumers.

Upper Panel: S&P 500/WTI ratio (blue line); 84 months Moving average of the S&P 500/ WTI ratio (red line); Lower panel: Relative performance of S&P 500 Index to S&P 500 Energy Index (green line).

In this context, Wall Street still has to realize the FED's impotence in an economy driven solely by government spending, which will inevitably harm consumers and investors. Therefore, it is not a surprise that the Wall Street consensus still expect 2 additional FED rate cuts by the end of the year with 74% probability and 5 rate cuts in 2025. Seasoned investors must remember that inflation-driven misery stems not primarily from the FED, but from reckless regulations imposed by politicians pushing to ‘build back better’ for the kleptocrats and kakistocrats of the world. In this context, whether the FED cuts rates remain almost irrelevant; the real issue is stopping those who mismanage the economy under the pretence of climate change and DEI while fuelling forever bankers’ wars to enrich their plutocratic allies. Regardless of who occupies the White House next, Powell and his PhD colleagues know that interest rates always rise during wartime. The misguided Wall Street bankers will once again be wrong in thinking rate cuts will solve economic problems, which will only worsen under ‘Kamunism.’

Beyond the impact of the business cycle on the economy and financial markets, with the cycle itself being better understood through the lenses of energy efficiency of an economy, which can be proxied by the relative performance of the country's stock market against the price of oil in its domestic currency and the quality of a currency as a store of value, measured by the relative performance of gold in the local currency compared to the domestic bond market, liquidity is what drives markets. Just as blood is essential for the human body to stay alive and alert, liquidity plays a key role in sustaining the life and performance of the economy and financial markets throughout the 4 quadrants of the business cycle.

Liquidity is undeniably important to navigate the business cycle. Global liquidity must be monitored because, for the most part (outside of crises), national sources of liquidity are fungible, meaning they flow across borders. Global liquidity represents roughly a $170 trillion funding pool, which can be measured by assessing sources of funds from the assets side of the private sector balance sheet. This includes the short-term liabilities of credit providers, such as banks and shadow banks, as well as the cash flows of households and corporations. Since the focus is on flows through asset markets, the funding-based definition of liquidity emphasizes the financial sector. It extends beyond traditional money supply measures like M1. The cash flow equation illustrates the math behind the definition of liquidity. Unlike most economic statistics, which reflect net flows, liquidity is a gross balance sheet concept that measures the capacity of capital. The equation shows that sources of funds, or liquidity, namely savings (S) and changes in financial liabilities (ΔFL), must, by definition, equal the uses of funds, such as new capital investment (I) and changes in the value of asset holdings (ΔFA). It follows that the overall private sector balance sheet can expand (i.e., both FA and FL increase) while net savings (S - I) remain unchanged. In this case, liquidity expands independently of savings. Sources of funds (S + ΔFL) typically drive the uses of funds (I + ΔFA), but rising collateral values (ΔFA) can also trigger second-round effects that further expand lending and, in turn, boost liquidity.

This elasticity in the liquidity-creation mechanism is crucial. It surpasses conventional explanations of excess liquidity, such as the widely quoted 'savings glut' theory, which became a popular explanation for the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis. This theory, associated with former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, argued that abundant Asian savings flows inflated the US asset bubble. However, this seems unlikely in terms of scale. Instead, Asian savings flows (S) may have initially triggered an increase in liquidity that was later amplified by aggressive lending from banks and shadow banks (ΔFL → ΔFA → ΔFL), creating a massive wave of liquidity.

The elasticity of the liquidity mechanism plays a dominant role in the liquidity cycle, with some referring to it more accurately as a 'banking glut' rather than a 'savings glut.' Liquidity, like the economy, is cyclical. Global Liquidity can be measured as a normalized index (GLI) ranging from 0 to 100, with a mean of 50, to track its momentum over time and across countries. A chart plotting the GLI against a repeating 65-month cycle (estimated using Fourier analysis from 1965-2000 and extrapolated since), shows that the Global Liquidity Cycle is expected to peak around September 2025, following the trough in December 2022.

The 65-month cycle (between 5 and 6 years) can be explained by the fact that this frequency represents the turnover of debt, making it the debt refinancing cycle. The average maturity of debt in the world economy is about that length of time. As debt is rolled over, it creates cyclical movements, which is what we are seeing now. The cycle bottomed in October 2022 and is expected to peak in late 2025.

To understand how the world has been flooded with liquidity over the past years, investors can first look at a rough proxy for the global money supply by summing up the M2 of major economies such as the United States, the Eurozone, China, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Taiwan, Brazil, Switzerland, Australia, Mexico, and the UK. You don't need a PhD in macroeconomics or work for a central bank to see that over the past 20 years, this proxy for liquidity across major economies has more than tripled, from roughly $30 trillion in 2002 to about $105.5 trillion as of October 19th, 2024. At the same time the 65 months rate of change peaked in 2009; 2011; 2014 and mid-2021, period which coincided with financial crisis around the world.

Global Money Supply Proxy (blue line); 65-months Rate of Change (red histogram).

Aside from the liquidity created by central banks, there is also liquidity generated by governments, which reflects their fiscal policies. This can be proxied by the government debt issued by the three largest economies in the world: the US, China, and Japan. Over the past 20 years, the debt issued by these three governments has more than quadrupled, rising from less than $8 trillion in late 2004 to more than $45 trillion as of the end of October 2024. Here as well, looking at the 65-months rate of change it peaked in early 2013 before troughing in late 2019 and since then rising to a gargantuan 69%.

US + China + Japan Government debt (blue line); 65-months Rate of Change (red histogram).

Focusing on the US alone, since it has held the imperialist privilege of being the reserve currency since the end of World War II, the money supply in the US, proxied by M2, and US government debt have both increased exponentially over the start of this decade. On a longer time horizon, the US money supply rose from less than $500 billion at the end of 1964 to more than $21 trillion (almost 42 times) in around 60 years, while US public debt more than doubled over the past 12 years to exceed $35 trillion.

US Money Supply (blue line) & YoY Rate of Change (green histogram); US Government debt (red line) & 65-months Rate of Change (purple histogram).

An anecdotal observation illustrating how public debt has been used for political purposes is that US government debt rose by more than half a trillion dollars ($500 billion) since the end of August. This demonstrates that no amount of public money is ever enough to lure more voters into the false illusion that government spending will lead to prosperity under the next president whoever he or she is.

With $35.8 trillion in debt, US government debt is increasing by $1.0 trillion every 100 days. Based on the latest budget statement, the government now spends more than $80 billion on gross interest each month. For fiscal year 2024, which ended on September 30, US interest spending hit an all-time high of $1.133 trillion. This is the first time in history that annual interest on U.S. debt has surpassed $1.0 trillion. To put this in perspective, gross interest on the debt has grown by 30% year-over-year and now exceeds defense spending, as well as income security, health, veterans' benefits, and Medicare. It has become the second-largest US government outlay, trailing only Social Security, which costs approximately $1.5 trillion annually.

For the fiscal year 2024, ending September 30, the US Treasury reported a $1.833 trillion budget deficit, the third highest on record, primarily driven by government spending. This deficit increased by 8%, or $138 billion, from the $1.695 trillion reported in 2023. The largest deficit occurred in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by $2.772 trillion in 2021 as cleanup efforts took place. The spending included a reversal of the decision to forgive $330 billion in student loans after the Supreme Court deemed the action unconstitutional. Democrats are now blaming Republicans for ‘tax cuts that led to low revenue levels and increased debt.’ While the reality is higher spending and tighter regulations which are burdening taxpayers. At 6.3% of nominal GDP, the deficit remains lower than during the COVID crisis. However, with slower economic growth and rising inflation and war driven misery in the quarters to come, everybody should expect the deficit to continue increasing in dollar or percentage of GDP terms in the coming quarters.

US Treasury Federal Budget Deficit/Surplus (blue line); US Treasury Federal Budget Deficit as % of US GDP (histogram) & US Recessions.

For those who believe taxing the ‘rich’ through measures like taxing unrealized gains will solve fiscal issues, they should think twice. The combined wealth of the 10 richest Americans, around $1.7 trillion, would only cover roughly 1.5 years of U.S. government interest expenses or barely the last yearly US budget deficit.

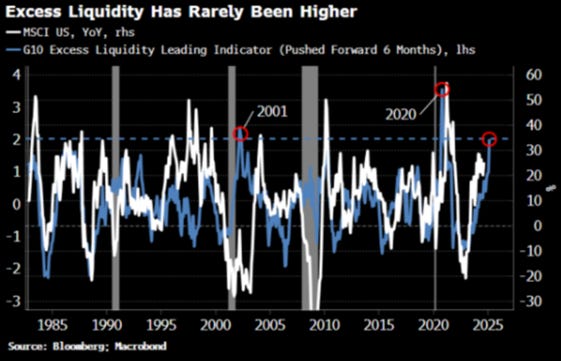

In this context it is fair to acknowledge that in the short-term, liquidity conditions in the US and globally are strengthening, with G10 excess liquidity reaching levels seen only twice in the past 50 years. Stimulus in China and easing in the US will enhance the positive backdrop for risk assets in the short-term. However, excessive liquidity will inevitably lead to frothy markets. Indeed, as everyone knows the post-pandemic cycle has been volatile, and it may become even more so, as excess liquidity, measured by real money growth outpacing economic growth, has hit a recent high, surpassed only in 2001 and 2020.

Outside the US, the stimulus in China which still needs to be quantified and implemented could be a game-changer for the global liquidity landscape. While China doesn't directly contribute to G10 excess liquidity, its money supply is likely to grow from depressed levels, further enhancing the positive liquidity backdrop. Historically, China has been a major driver of liquidity, contributing up to 70% of global money growth during the Global Financial Crisis. However, in the past two years, it has significantly hindered global money growth.

Looking deeper at the China's economic model, it is in the process of shifting towards consumption, but recent government stimulus measures appear inadequate and unsufficient to accelerate this process which is part of the Make China Great Again agenda. While a proposed trillion Yuan in fiscal stimulus sounds significant, it is minor compared to the US.'s $2-3 trillion spent during the 2008 financial crisis. What China requires is a massive monetary and fiscal stimulus to bring the economy out of its inflationary bust by improving its energy efficiency and restoring the Yuan as a good store of value compared to gold. Despite the common belief in the western world that China aims to develop the Yuan as the next reserve currency in a de-dollarizing world, Chinese elites understand the cost of managing a global reserve currency. Instead, China is working to establish a decentralized monetary system within the multipolar mercantilist Global South, where each member can trade in their own currency, avoiding the imposition of a new centralized ‘operating system’ like the USD-centric world built around SWIFT after World War II. In this scenario, China will seek to position the Yuan as a credible store of value against other currencies from the Global South, with the USD reference losing relevance once China's economy is fully de-dollarized, likely post-2028. As the Chinese government has always been hesitant to issue money out of thin air, as its fiscal spending relies on existing savings rather than new money creation, the timing to exit the current inflationary bust could still require investors to have a taoist patience which is far behind any time horizon of all investors, especially in the western world. Investors will remember that historically, similar situations have precipitated economic crises, as seen in Northeast Asia in the 1990s. Similarly, in early 2008, China tightened monetary conditions before the Olympics, inadvertently pushing borrowers into the eurodollar markets, which contributed to the global financial crisis. A similar scenario is on the cards if China continues to tighten credit while increasing fiscal spending. Recent data indicates that, despite claims of injecting liquidity, they are actually withdrawing funds from money markets, suggesting a tightening of conditions rather than economic stimulation.

A quick look at PBOC liquidity injections alongside a nowcast of world GDP shows that while the Federal Reserve's actions significantly impact financial markets, China's policies affect the global economy and commodity prices. Recently, liquidity injections have started to decline, indicating potential slowdowns in the world economy and increased pressure on financial markets. This comes at a time when China is struggling to implement effective policies to address its substantial economic imbalances. As a dollarized economy, Chinese banks hold significant dollar positions in both assets and liabilities, with much of their trade conducted in dollars. This situation is critical, as China can influence global dollar demand by pulling liquidity from the system at inopportune times for the rest of the world.

In this context, it’s evident that the FED and other central banks are laying the groundwork for the next credit disaster. US monetary policymakers may feel relieved after completing a vigorous hiking cycle without crashing credit markets, but the swift easing already in motion is distorting debt valuations and flooding markets with liquidity. The Federal Reserve could adopt ‘mission accomplished’ as its slogan after stifling inflation without derailing the economy or shutting down debt markets. While defaults and bankruptcies have increased slightly, the damage has been less severe than feared, despite funding costs doubling for weaker borrowers. If anyone still has doubts about the stickiness of inflation, a simple computation of autocorrelation and estimates of the number of months that shocks persist or echo through the pricing structure show that this indicator, which averaged 5 to 6 months over the past 74 years and peaked in 1980 at 56 months, has once again increased to a worrying level of 8.6 months. This indicates, for those willing to listen, that the fight against inflation is far from being a ‘mission accomplished,’ as propagandistically claimed by the Fed chairman over the summer.

Over the past few years, the FED has become known for spreading the forward illusion by injecting shadow liquidity behind the scenes. This has been highlighted in financial media as ‘stealth easing’ or ‘Not QE, QE.’. To understand what is happening in terms of debt monetization within the US system, let's examine the FED's actions, The blue line represents the absolute size of the FED's balance sheet. The FED discusses its quantitative tightening (QT) policy in the context of this total balance sheet, stating that if the blue line is decreasing, they are effectively undertaking QT. However, this perspective is insufficient because not all parts of the balance sheet create liquidity and liquidity can be injected into financial markets by using other means that the balance sheet such as the Treasury General Account and the Reverse Repo Program or like during the 2023 bank walk the use of the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). The red histogram which is a rough proxy of the FED’s liquidity and calculated by adding the liquidity available from the Treasury General Account and the Reverse Repo Program shows that ‘real liquidity’ the evolution of the FED balance sheet can diverge significantly. Indeed these 2 trends have deviated significantly from those projections. Two key events have altered the Fed's approach:

The British Gilt Crisis (September 2022): The UK sovereign debt market experienced a sharp sell-off after a poorly executed budget announcement, leading the Bank of England to pivot from QT to QE. This event served as a wake-up call for policymakers, highlighting the vulnerability of sovereign debt markets to missteps. Ultimately, the primary goal for the FED and the Treasury is to maintain the integrity of the U.S. Treasury market, with inflation and employment mandates taking a back seat.

The SVB Crisis (March 2023): Following this crisis, liquidity increased significantly, marking a clear inflection point. The shadow liquidity rose sharply over that period with even the FED balance expanding as shadow liquidity injection were required to save the financial system from the disastrous effect of the ‘bank walk’.

Overall, these developments illustrate how the FED’s liquidity measures have evolved in response to crises, impacting the broader financial landscape and cannot be only summarized as the evolution of the FED balance sheet.

FED Balance Sheet (blue line); USD Liquidity proxy Index (red histogram).

What the mass media refers to as ‘Not QE QE’ suggests that while the FED claims not to be engaging in quantitative easing, they effectively are. The outlook for the next three months appears positive, primarily due to the impending reimposition of the US debt ceiling on January 2, 2025, which will require the Treasury's general account at the FED to be reduced from its current level of about $850 billion to the historical norm of around $250 billion. This could inject approximately $500 billion back into financial markets, enhancing liquidity as year ends.

Additionally, authorities have recently relaxed the rules governing stress tests for US banks, allowing them to incorporate access to the discount window, loans from federal home loan banks, and the standing repo facility into their assessments. This means banks may not need to hold as many reserves at the FED. A decline in bank reserves at the FED will allow them to utilize these funds in other areas, such as the Treasury market and therefore is also enhancing liquidity in financial markets. In essence, shadow liquidity is increasing under the guise of ‘Not QE QE.’ as besides the partisan and politically driven interest rate cuts, the FED has been actively injecting liquidity behind the curtain. On the other hand, uncertainty around the outcome of the presidential election and the expected chaotic change of power coming by January 21st, 2025, will inevitably create social unrests which in financial markets would translate into much higher volatility and in the economy in much higher inflation, driven by shortages.

NY FED Reverse Repo Data (blue line); US Treasury General Account (red line); FED Balance Sheet (green line).

For the time being, markets are pricing in sustained rate cuts, offering vulnerable companies’ relief from elevated interest payments, but a credit market reckoning has only been postponed. The surprising 50-basis-point rate cut from the FED in September triggered a rally in junk corporate bonds, with buyers eager to seize the highest yields in decades, compressing spreads on CCC-rated bonds to their tightest since April 2022.

Even before easing began, debt market stress, as measured by the New York FED, was near historic lows, with credit spreads highly compressed due to demand outstripping supply, even as companies issued record volumes of debt. Corporate debt clearly didn't need additional stimulus; however, substantial easing and optimistic economic forecasts have created excess speculation. This environment encourages buyers and makes it easier for risky companies to take on more debt.

While two years of high rates eliminated many unsustainable companies, many others have managed to delay their reckoning. This year's rally in junk debt markets, fuelled by dovish rate expectations, has provided lifelines to numerous firms. Some have turned to private credit as a last resort, leaving hidden risks in the market. Currently, one-third of Russell 3000 companies with listed interest expenses failed to generate sufficient operating income to cover their interest costs in the past year, marking them as ‘zombie borrowers.’ This group holds a combined $1.26 trillion in debt, with 471 firms neither profitable nor cash-flow positive over the same period.

If bull markets thrive on a ‘wall of worry,’ financial crises often crash against a ‘wall of debt.’ On this matter, no one needs to be a PHD working for a central bank to understand that the world is approaching another crisis, driven not just by rising interest bills but by the looming challenge of rolling over the world's massive debt, estimated at $350 trillion. With the liquidity cycle peaking, the years 2025 and 2026 will be particularly difficult for investors, as they must contend with not only increasing concerns about future growth and inflation but also a significant maturity wall of corporate debt refinancings from years of low interest rates. This pattern has historically triggered financial meltdowns, as seen in the 1997-98 Asian Crisis and the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis.

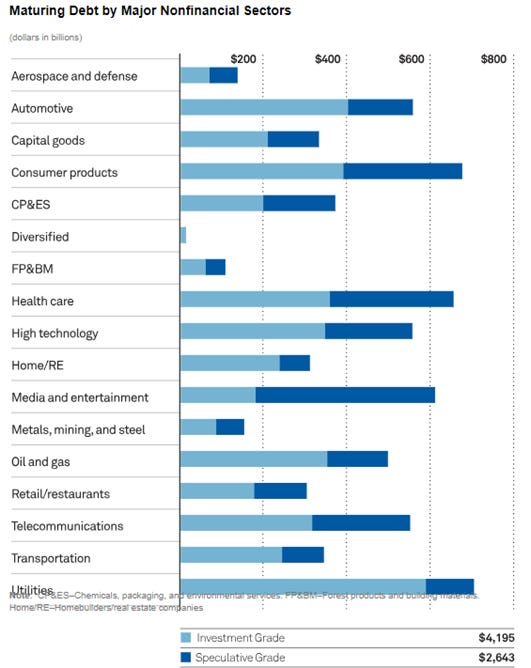

According to the latest estimates from S&P Global Ratings, approximately $11 trillion of non-financial S&P-rated debt is expected to mature in 2025 and 2026, with $4.888 trillion in the US, $4.264 trillion in Europe, and $1.853 trillion in the rest of the world.

Looking at the details by sectors, debt is mostly concentrated in consumer products, healthcare, media and entertainment, and utilities, with the majority being investment-grade.

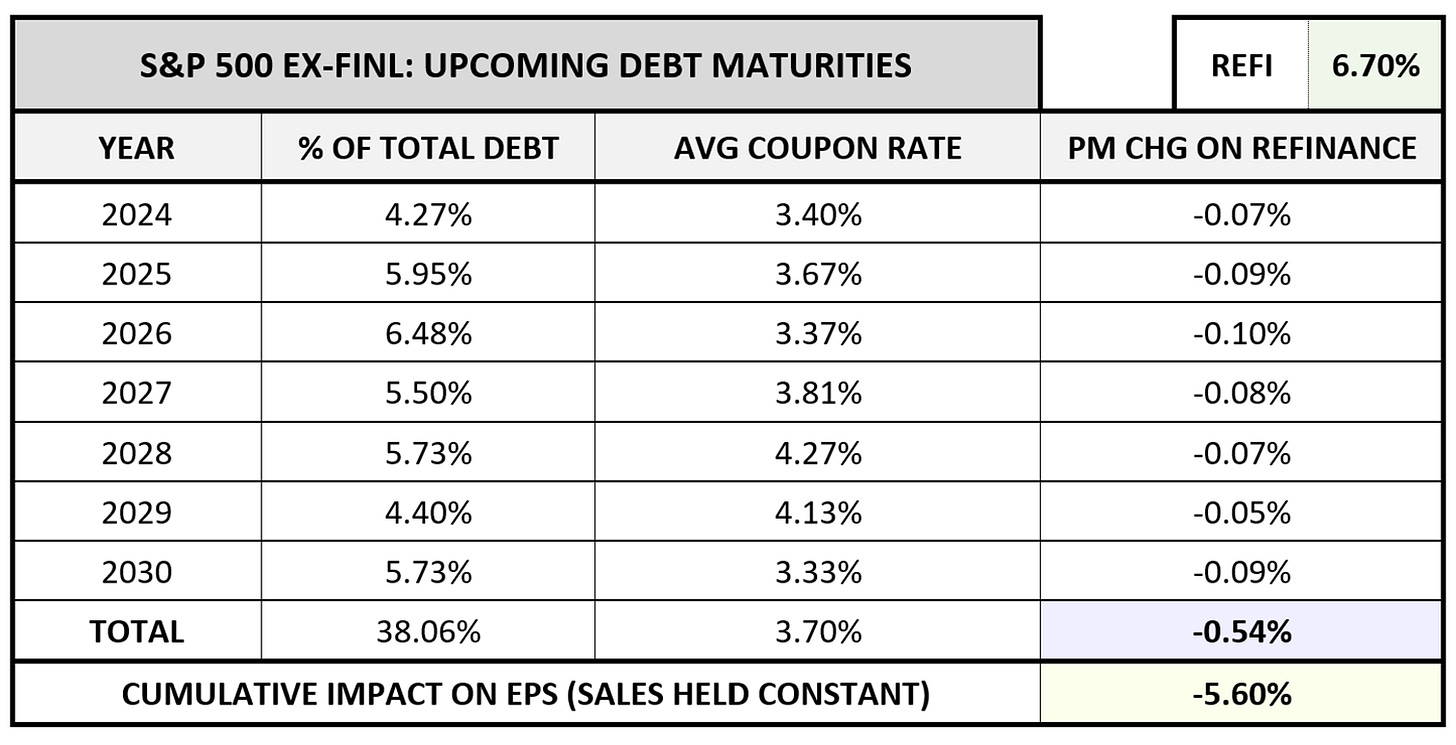

While the corporate sector remains relatively insulated from the immediate impact of rising interest rates, having issued substantial medium- and long-term debt during the low-rate environment of the last decade, the ‘maturity wall’ highlights the share of fixed-rate S&P 500 debt maturing each year as a percentage of total existing debt (both variable and fixed-rate). In plain terms, about 4% of S&P 500 debt matured in 2024, 6% will mature in 2025, and 6.5% in 2026. By 2030, roughly 38% of the total existing stock of S&P 500 debt will have matured.

A look at the net debt-to-sales ratio of the S&P 500 (excluding financials) shows that while it's below the peak of nearly 40% at the start of this decade, it remains at 32.5%, similar to mid-2019 levels and well above the 15% seen in 2008. However, with the U.S. 10-year yield rising from around 2.5% to over 4.2% by October 2024, any debt refinanced in the near future will face significantly higher coupon rates compared to the past 15 years.

Net debt to sales for S&P 500 ex financial index (blue line); US 10-Year Yield (red line).

To estimate the earnings impact of upcoming debt maturities, we can approximate the cumulative effect on EPS by multiplying the percentage of debt maturing each year by the total debt as a percentage of sales, assuming sales remain constant.

Over the next seven years (2024–2030), the cumulative decline in profit margins is estimated at 0.54%, leading to a 5.6% drop in earnings and EPS, assuming all other factors like sales and share counts remain constant. While those variables will likely change as the S&P 500 grows, this 5.6% decline reflects the impact of higher interest rates alone. This decline is not an annual loss but a cumulative one, translating to an average annual drag of about 0.82%, enough to reduce the index’s returns below historical averages but not drastically alter overall performance. The calculation is based on a 6.7% nominal refinancing rate, 3% higher than the current 3.7% average coupon rate. If long-term rates rise further, the EPS reduction could be even greater.

It is not only US corporations that will have to refinance debt. Indeed, the US government alone has more than $5.5 trillion and $3.3 trillion of debt to refinance in 2025 and 2026, respectively. This does not take into account the new debt that will be issued by the new tenant of the White House to finance the ‘forever bankers wars’ and the rising government spending that will inevitably be required to support the economy, even if it can miraculously avoid further economic slowdown.

Investors must remember that based on the latest monthly statement of the US public debt published by the US Treasury department, while 89% of US government debt outstanding is fixed rate, 22% are bills; 50% are notes and 17% are coupons.

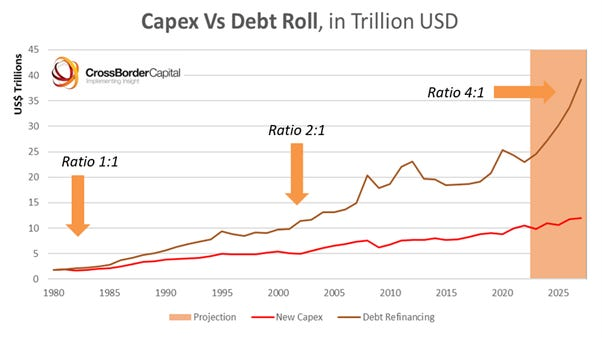

Investors must understand that financial markets have increasingly become mechanisms for debt refinancing, but to work as such mechanism they must deal with the cyclical nature of liquidity which needs to be adequate to meet the exponential evolution of the growth of debt. In a few words, a stable financial system requires a balanced ratio between total debt and available liquidity; too much debt risks refinancing crises, while excessive liquidity can lead to inflation and asset bubbles. Policymakers must find a middle ground. Historically, capital markets were viewed as mechanisms for new financing, but this has been changing since the start of the millennium. In 1980, the annual debt roll in advanced economies was roughly equivalent to new capital expenditures (capex). By 2000, refinancing needs had doubled, and by 2026, they will be nearly four times the projected new capex. In today’s environment, about 75% of trades in financial markets are for refinancing existing debts. With an average maturity of seven years, this means approximately $50 trillion of existing debt must be rolled over annually, necessitating greater capacity within the financial sector and larger volumes of global liquidity. This shift indicates that capital markets are increasingly functioning as debt refinancing mechanisms rather than sources of new capital investment.

While global liquidity has surged, driven by rising bank lending, improving collateral, and central banks eager to ease monetary conditions, the looming maturity wall cannot be ignored. Latest estimates indicate a $16.1 trillion increase in global liquidity over the past year, with a notable $5.9 trillion rise since June, bringing the total to $175 trillion, about 1.5 times global GDP. This reflects a robust 15% annualized expansion. However, markets will demand even more liquidity to support the growing appetite for debt. Debt rollovers require balance sheet capacity across the financial sector, which fundamentally means liquidity. Looking back, since 1980, the ratio of advanced world debt to global liquidity has averaged 2.5 times, peaking at 2.9 times during the 2008 crisis and again during the Eurozone banking crisis (2010-12). Refinancing tensions emerge when this ratio significantly exceeds the long-term average of 250%. While it approaches this threshold in 2025, it is projected to exceed it in 2026. By 2027, this debt-to-liquidity ratio is likely to surpass 2.7 times. Alarmingly, the maturity wall, which measures the annual debt rollover, will not only exceed the average but will also increase by nearly 20%, reaching over $33 trillion, or three times the annual capital expenditure by advanced economies.

This wall of debt must be put in the context of the weaponization of USD assets and the parabolic increase in government spending. This situation has pushed the FED and Treasury to collaborate to stabilize the bond market, striving to ease stress as reflected in the MOVE Index, which measures volatility in the US Treasury market. Generally, a MOVE Index reading can be interpreted roughly as annualized volatility: for example, a reading of 100 suggests about 10%, while 160 indicates 16%. The structurally elevated MOVE Index since the start of the decade highlights the volatility of this crucial asset class which is US Treasury give that historically, the price of a dominant economy's debt has been a key indicator of the ability of that economy to generate enough liquidity to keep the world financial markets and economies afloat. In this context, the primary focus of the FED and the Treasury is to reduce the MOVE Index, employing strategies like reverse repos and injecting liquidity, alongside Treasury buybacks, which swap older bonds for newly issued ones to enhance market liquidity. Investors must understand that lower bond market volatility is vital because it increases the value of collateral, primarily US Treasuries, which drive global liquidity creation. Since the Global Financial Crisis, most lending has been collateral based, making stable collateral essential for liquidity expansion. Thus, the FED and Treasury's efforts to reduce volatility in the bond market are critical for overall financial stability, far more significant than monitoring the VIX Index.

US Government Liquidity index (blue line); MOVE Index (red line); Correlations & US recessions.

However, the pressures in the Treasury market stem from the enormous deficit, which negatively impacts bond volatility and yields. To assess the situation, a comparison between the 10-year Treasury yield (in orange) with a synthetic estimate derived from the agency mortgage market (in black) shows that while the agency mortgage market is considered risk-free, similar to Treasuries, and is held by the Federal Reserve and foreign central banks. It typically offers a higher yield and greater convexity. When adjusted for comparison, the black and orange lines usually overlap, but significant dislocations indicate underlying issues which has historically led to financial crisis such as in 2008 and 2020.

Looking at the spread between 30-year agency mortgages and the 10-year US Treasury yield, along with the amount of Treasury bill issued, it appears that large deviations between the agency market and Treasury market typically indicate a scarcity of coupon debt due to the Treasury issuing an abundance of short-dated securities, which has surged over the past 12 months. Indeed, since the end of 2022, the average maturity of auctioned debt has decreased by 1.2 years, resulting in more short-dated paper. This shift has significant implications for the US financial system. If the 10-year Treasury yield is manipulated and remains artificially depressed by about 100 basis points, it creates a longer inverted yield curve with a shallow slope. Consequently, this manipulation has prevented the typical yield curve inversion that signals impending recessions, leading to a perception of slow growth without a recession despite the underlying realities.

Spread between US 30-Year Mortgage rate & US 10-Year Yield (blue line); US Total Debt Outstanding Bills (red histogram).

Additionally, buying in the TIPS market has been shifting, with breakeven inflation rising from the traditional 1% to 2% which prevailed during the period between 2015 and 2020 to between 2% and 3% since the start of the decade. A change that was most likely also driven by structurally higher levels of commodity prices as proxied by the Bloomberg Commodity Index.

Bloomberg Commodity index (blue line); US 5-year Break even rate (red line).

Looking at US debt monetization, while the US may be the ‘cleanest shirt in the laundry’ compared to Europe, and Japan, it faces significant challenges. A critical issue with issuing substantial short-term debt is that it is typically purchased by banks instead of pension funds. When banks buy this debt, it leads to monetization, expanding their balance sheets and increasing the money supply. In fact, about three-quarters of this year's increase in the US money supply has stemmed from debt monetization, as banks acquire agencies and Treasuries, inflating their portfolios.

As ‘Kamunism’ has already started before it was officially institutionalized, Milton Friedman would be turning in his grave if he saw these numbers, as they point to a future inflation disaster. Indeed, investors must always remember that ‘Inflation is the one form of taxation that can be imposed without legislation’.

The break-even inflation analysis chart reveals that the bond market's implied 10-year inflation rate in the US, calculated by subtracting the TIPS 10-year yield from the conventional 10-year yield, currently indicates an average break-even inflation of around 2%, exactly where Jay Powell wants it. However, everyone knows that this figure is biased due to the artificial suppression of Treasury note yields by Janet Yellen's policies, which means that true break-even inflation rate is roughly 1% higher than the market-implied break-even inflation. This aligns with the University of Michigan's inflation survey, which shows consumers expect inflation near 3% over the next 5 to 10 years.

Spread between US 10-Year Yield and US 10-Year Breakeven Yield (blue line); True break-even inflation rate (red line); University of Michigan 5-10 consumer inflation expectations (green line).

In a nutshell, central planners, particularly the Treasury, are distorting price signals in the bond market to lure investors into a forward illusion narrative that they have accomplished their mission in the fight against inflation while continuing to issue gargantuan level of debt to finance their reckless government spending. This is akin to a pilot relying on faulty instruments, as policymakers have been setting policy and lending rates based on artificially low yields priced by the bond market. There is no doubt that policymakers are aware of this manipulation, as evidenced by the recent shift in the tenor of bond issuance. This shift occurs due to the weaponization of USD assets, leading to high demand for short-dated government bonds from banks and credit providers such as hedge funds. Indeed, banks receive increased deposits and need to match them with offsetting assets, making short-dated government bonds the ideal choice.

US Total Debt Outstanding Bills (blue line); US All Money Market Fund Total Net Assets (red histogram).

First and foremost, and unsurprisingly given the weaponization of USD assets, foreigner demand of sovereign debt has been declining quite significantly relative to net insurances in the past years in this period of craziness in government spending.

Secondly, a significant portion of US Treasuries is indeed being purchased by hedge funds, which are custodizing their assets in countries like Ireland; Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands. Conversely, foreign institutional investors are not buying Treasuries to the same extent as before; China and Japan, in particular, have reduced their holdings.

US Treasury Holding by Japanese (blue line); Chinese (red line); Luxembourg (green line) Cayman Island (purple line); Ireland (yellow line) investors.

The most disturbing aspect for a country like the US, which has depicted itself as an invincible empire, is that maintaining such dominance requires an adequate level of savings to fund productivity-enhancing capital investments. Relying on the kindness of overseas strangers to provide that funding is dangerous, if not reckless, especially for a nation like America, which is diligently debasing and weaponizing its currency. This behaviour does not inspire confidence among offshore investors over the long-term. The fact that this appalling situation is occurring during a time of low unemployment and, if official statistics are to be believed, healthy economic growth is unprecedented. It also undercuts the constant raving on financial channels like CNBC about the exceptional strength of the U.S. economy.

With hedge funds currently buying Treasuries through arbitrage trades, aggressively selling futures while purchasing cash Treasury bonds, this strategy relies on low market volatility. Eventually, true inflation will emerge, and higher inflation rates will impact those who have made bets based on the current distorted yields.

ICE BofA Move Index (blue line); US 10-Year Yield (red line); US CPI YoY change (green line); Correlation between ICE BofA Move Index & US 10-Year yield.

Concerns about Treasury liquidity have lingered since the pandemic, when in March 2020, the Federal Reserve had to implement emergency measures to stabilize a severely impaired Treasury market. Recently, various liquidity indicators, such as increased order-book depth, have suggested that risks are easing.

Treasury market liquidity has not returned to pre-pandemic levels, with order-book depth still below 2019 levels and Bloomberg’s liquidity index remaining elevated. This leaves liquidity vulnerable to rising event risk and heightened volatility, worsened by constrained primary-dealer balance sheets. A recent NY Fed paper shows that while yield volatility drives liquidity, constrained dealer capacity, now near highs relative to total debt, is a key factor in liquidity deterioration. When balance-sheet constraints are high, they primarily explain worsening liquidity, even when excluding volatility.

Most of the extreme balance-sheet strain occurred in March 2020 when the pandemic disrupted markets. While that level of risk is not anticipated today, rising volatility and constrained dealer balance sheets still pose a significant threat to Treasury market liquidity. Primary dealers, who facilitate almost all Treasury trades, are key to maintaining liquidity. The current issue stems from the prolonged yield curve inversion, which has led to a ‘buyers' strike’ among carry traders, as negative carry deters them from purchasing Treasuries. This leaves dealers with excess inventory from government auctions, clogging their balance sheets and increasing their reliance on repo funding. As shown in the chart, dealer inventories have swelled during this inversion.

Primary Dealer Positions Outright US Government Securities Inventory (blue line); Spread between US 10-Year Yield and USD/JPY 3-month hedging cost (axis inverted; red line).

In this context, curves like 2s10s and 5s30s are less relevant for market analysis and recession prediction compared to those tied to funding points, such as 3-month vs. 10-year or the 3-month FX-hedge cost for USDJPY vs. 10-year. While 2s10s may have dis-inverted, real relief for dealers won’t come until these key curves dis-invert, easing pressure on their balance sheets. Other factors, such as re-emerging inflation risks and a growing fiscal deficit, also threaten Treasury market liquidity. Inflation, driven largely by a profit-price-wage spiral, remains a persistent challenge, and renewed stimulus in China could push US CPI back above target, increasing inflation volatility and worsening Treasury liquidity.

Adding to the liquidity strain, the market is absorbing increasing issuance of longer-duration notes and bonds as the US government finances its $1.8 trillion fiscal deficit. While bill issuance, which was dominant in 2022 and 2023, has remained flat, the rise in longer-duration issuance is now putting further pressure on dealer balance sheets and overall market liquidity. Reflexivity in financial markets means that factors like yield volatility, balance-sheet constraints, inflation, government issuance, and Treasury liquidity can start to reinforce each other negatively. Rising yields pose risks for stocks, and in a worst-case scenario, the FED may need to intervene again. Treasury buybacks of off-the-run securities won't significantly improve overall market liquidity due to their limited scope.

In conclusion, with a significant maturity wall to finance in the next two years and the Federal Reserve will inevitably be forced to recognize higher inflation, which may slow the supply of liquidity, leading to a funding clash as debt needs to be rolled over with reduced liquidity. That’s why the focus should be on balance sheet capacity and liquidity rather than on the level of debt per se and the level of yields which have been distorted by the increased reliance on shorter maturity to finance an ever-increasing government debt. In this context, any spikes in the MOVE Index could unsettle these hedge funds and create a precarious situation for financial markets.

S&P 500 index (blue line); ICE BofA Move Index (axis inverted; red line) & correlations.

Circling back to the three financial ratios that really matter for depicting the business cycle and how to allocate portfolios across asset classes—the S&P 500 to gold ratio, the S&P 500 to oil ratio, and the gold to US Treasury index ratio—it is interesting to see how the total amount of USD liquidity, which could be proxied by adding the US government's total debt to the USD liquidity injected into financial markets by the FED and the Treasury, has impacted the evolution of these three ratios over history and how it has also influenced the gyrations of these ratios around their 84-month moving average. A short and sweet conclusion is that the more liquidity (debt or monetary liquidity) is issued, the higher the risks of monetary illusion (i.e., the S&P 500 underperforming gold and breaking below the 84-month moving average), and consequently, the more gold investors need to own and the fewer bonds they need, as their primary goal is to protect themselves against the currency debasement created by reckless policies from the government and the central bank. When the rate of change in liquidity slows down, the higher the risk that the economy becomes energy inefficient. In this context, if the US government and FED want to avoid the US to fall into an inflationary bust in the coming quarters, they will need to unleash additional tsunamis of liquidity to tackle the great wall of debt lying ahead.

WHAT’S ON THE AGENDA NEXT WEEK?

The week of Diwali in the Hindu world will keep macro and micro investors on their toes with the release of October's Non-Farm Payroll in the US and the PMI indices in the US and China. Investors will also be watching the Bank of Japan meeting. On the earnings front, 162 companies from the S&P 500 will release their quarterly reports, including 5 of the Magnificent 7 (Alphabet; Microsoft; META; Amazon & Apple), along with companies like Visa, AMD, McDonald's, and Caterpillar, among others.

KEY TAKEWAYS.

As Americans gear up for another trick-or-treat season, here are the key takeaways:

The BRICS summit solidified the emergence of a new world order, driven by China's manufacturing prowess, serving India's growing consumer economy, and fueled by access to cheap fossil energy from Russia.

The politically driven October Beige Book still failed to address the market-driven reality that the US economy is on the verge of shifting from an inflationary boom to an inflationary bust.

The flash estimate of the US PMIs showed that both manufacturing and services entrepreneurs are increasingly worried about the post-election environment.

Liquidity, the lifeblood of financial markets, has been expanding through private sector balance sheets and rising asset values, driving financial performance across the business cycle.

The elasticity of the liquidity-creation mechanism, driven more by aggressive lending than by a ‘savings glut,’ plays a key role in the liquidity cycle, with global liquidity expected to peak in September 2025 after its trough in December 2022.

Historically, the 65-month debt refinancing cycle, driven by the average global debt maturity, has significantly influenced liquidity movements.

Higher inflation and a wall of debt refinancing will drain liquidity from financial markets, raising a significant debt burden.

The FED, in partnership with the Treasury, has been injecting ‘shadow liquidity’ despite its claims of quantitative tightening, using recent crises and the upcoming US debt ceiling to justify efforts to smooth market volatility.

Savvy investors know that If bull markets thrive on a ‘wall of worry,’ financial crises often crash against a ‘wall of debt.’

As financial markets become increasingly driven by debt refinancing, the years 2025 and 2026 will pose challenges due to the need to roll over a significant portion of the $350 trillion in global debt, requiring substantial liquidity to avert financial crises akin to those of 1997-98 and 2008-09.

Issuing substantial short-term debt, primarily purchased by banks, leads to debt monetization, distorts bond market signals, and creates a false narrative of inflation control, while facilitating reckless government spending through artificially low yields.

As the US is about to shift from an inflationary boom into an inflationary bust, every equity rally should be sold, and investors should focus on buying the dips in energy producers while selling the strength in energy consumers.

In such environment, investors will once again need to focus on the Return OF Capital rather than the Return ON Capital, as stagflation spreads.

Physical gold remains THE ONLY reliable hedge against reckless and untrustworthy governments and bankers.

Gold remains an insurance to hedge against 'collective stupidity' and government’ hegemony which are in great abundance everywhere in the world.

With continued decline in trust in public institutions, particularly in the Western world, investors are expected to move even more into assets with no counterparty risk which are non-confiscable, like physical Gold and Silver.

Long dated US Treasuries are an ‘un-investable return-less' asset class which have also lost their rationale for being part of a diversified portfolio.

Unequivocally, the risky part of the portfolio has moved to fixed income and therefore rather than chasing long-dated government bonds, fixed income investors should focus on USD investment-grade US corporate bonds with a duration not longer than 12 months to manage their cash.

In this context, investors should also be prepared for much higher volatility as well as dull inflation-adjusted returns in the foreseeable future.

HOW TO TRADE IT?

With only seven trading days left before the year’s ‘political hell’ D-Day, the story of the past week was better-than-expected macroeconomic data, leading to a volatile market week. The Nasdaq ended as the only one of the three major equity indices in the green, while the Dow Jones underperformed both the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq. This marked the Nasdaq's seventh consecutive week of gains, fuelled by short squeezes in Tesla and Nvidia ahead of next week, when five of the other ‘Magnificent 7’ will release their quarterly earnings.

With the war cycle in ‘pause mode’ until markets closed on Friday, a false sense of calm has continued to lure institutional and retail investors into equities, though the upcoming November 5th election should make everyone nervous. The prospect of a ‘buy the rumour, sell the news’ event looms, especially if post-election surprises bring harsh economic policies under ‘Kamunism’ for the next four years or if election results are delayed to January 6th or even beyond rather than announced on election night. In this context, investors should prepare for heightened volatility that could potentially drive equity markets back to, or even below, their August 5th lows post-election.

Although the Nasdaq outperformed last week, it still hasn’t reached new all-time highs, while both the Dow and S&P 500 are showing signs of bearish reversals, which could signal what lies ahead post-election.

While any investor with common sense should prepare for reflation and an inevitable sector rotation in the coming months, last week's performance highlights the outperformance of growth sectors such as Consumer Discretionary and IT. Meanwhile, Energy and Materials, which are set to benefit from reflation remained unloved by myopic investors.

Everyone with a minimum of common sense knows that ‘today's corporate profits are tomorrow's investments and the jobs of the day after tomorrow.’ Everyone, that is, except the Keynesians, who were taught that growth comes from increased consumption, leading to the belief that the State must borrow to distribute unearned income and thus ‘stimulate growth.’ Their dogma asserts that prosperity rises as the State accumulates debt. Unfortunately, since 2008 and the great financial crisis, this policy has ceased to work, as debt is now growing much faster than wealth creation, leading us toward a historic debt crisis. The more the State goes into debt, the poorer those without assets (such as stocks and precious metals) will become.

In the current dystopian environment, anyone with a minimum of cynicism understands that in a world where inflation will undoubtedly become more embedded, what politicians have to do is basically sell Treasury debt at the lowest yield possible. In this context, they’ll probably create more misery to achieve their goals. Ultimately, the way to exit the wall of debt that will appear in 2025 is for central banks around the world to push for increased monetary inflation. Indeed, an increase in monetary inflation remains the only way politicians can address these huge demands on the fiscal purse. In layman’s terms, they’ve got to kick the can down the road, and that has also been the central banks’ playbook. Ultimately, that’s what they know how to do. So, the world should anticipate an 8% to 10% per annum trend growth in global liquidity. In this context, portfolios must be structurally allocated to deal with this new trend in monetary inflation, meaning that portfolios must have a significant allocation to assets that benefit from this monetary inflation, such as those available in limited quantities like physical gold, silver, and other commodities. At the end of the day, physical gold, by definition, is the only asset with more than two millennia of history demonstrating its ability to hedge government risks.

Outside of precious metals and other commodities available in limited supply, prime residential real estate can be considered a scarce asset, as there will always be a premium for real estate in prime locations, provided that the governments ruling these areas do not become extremely rogue in their treatment of asset owners and that conflict does not destroy the value of this prime residential real estate. Investors looking at real estate must also remember that interest rate will be structurally much higher in a wartime and therefore investors must own these assets free of debts or with a fixed rate over a tenure which allow them to reimburse their mortgage as soon as possible based on their financial wealth.

In addition to real assets, equities of companies with an economic moat and a low-leveraged balance sheet are also ways for investors to hedge against rising monetary inflation. However, when investing in these stocks, investors must remember that equity markets have been in a bull market for two years, and historically, at this stage of the bull market, markets have recorded more than 80% of their ultimate gains on average, indicating that most of the gains from this equity bull market could already be behind us. With many uncertainties, including geopolitics and the outcome of the US presidential election, investors should be prepared for a choppy end to 2024 and a turbulent year in 2025 and beyond.

Investors must also remember that the current favoured method of equity ownership—indexing—means that they are inherently betting against a significant rise in fossil fuel prices. As the war cycle intensifies, which has historically been favourable for gold and commodities like oil, it is prudent for anyone with a basic understanding of financial history to favour energy producers rather than energy consumers in their equity allocation, without neglecting the quality of their investments. In fact, most energy producers that have had their capital expenditures constrained by tighter regulations related to the climate change scam, have strengthened their balance sheets and improved their ability to generate positive free cash flow across the commodity cycle, placing them in an enviable position for the upcoming increase in oil and other commodity prices. Therefore, in addition to holding more than the recommended 25% allocation to gold in the Browne Portfolio, the equity allocation should be tilted toward these energy producers with strong balance sheets and the ability to generate positive free cash flow throughout the commodity cycle. On the contract side of the Browne Portfolio (cash and bonds), allocations should be kept minimal and invested only in short-dated (not exceeding 12 months) investment-grade corporate paper of companies with low leveraged balance sheets and which can be described as servicing the US economy's strategic needs.

If this report has inspired you to invest in gold and silver, consider Hard Assets Alliance to buy your physical gold:

https://hardassetsalliance.com/?aff=TMB

At The Macro Butler, our mission is to leverage our macro views to provide actionable and investable recommendations to all types of investors. In this regard, we offer two types of portfolios to our paid clients.

The Macro Butler Long/Short Portfolio is a dynamic and trading portfolio designed to invest in individual securities, aligning with our strategic and tactical investment recommendations.

The Macro Butler Strategic Portfolio consists of 20 ETFs (long only) and serves as the foundation for a multi-asset portfolio that reflects our long-term macro views.

Investors interested in obtaining more information about the Macro Butler Long/Short and Strategic portfolios can contact us at info@themacrobutler.com.

Unlock Your Financial Success with the Macro Butler!

If this report has inspired you to invest in gold and silver, consider Hard Assets Alliance to buy your physical gold:

https://hardassetsalliance.com/?aff=TMB

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.

" if China continues to tighten credit while increasing fiscal spending. Recent data indicates that, despite claims of injecting liquidity, they are actually withdrawing funds from money markets, suggesting a tightening of conditions rather than economic stimulation"

Why arw they tightening credit conditions ?

is there any free resource available, for measuring total Global liquidity?